|

Land History Geomorphic Regions Geomorphic Tour Soil science |

Geomorphic Tour:

The shape of the region

In This Section:

Lowlands | Slopes, ridges, and the Cody Scarp | Highlands: Tallahassee Hills

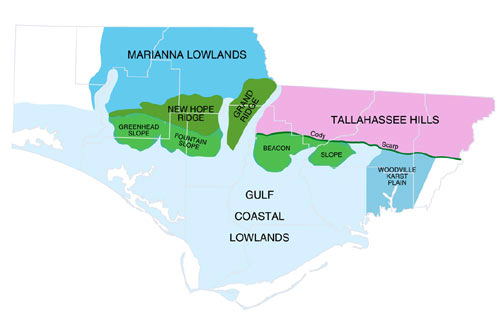

A general geomorphic map of the ARROW region. Blue areas are lowlands, green are ridges and slopes, and red are highlands. (Map created by Thomas Perrin based on information provided by the Florida Geological Survey.) |

The Gulf Coastal Lowlands region is the largest geomorphic region in the Panhandle and, for that matter, in Florida. It starts near Pensacola and extends all along Florida's west coast as far as Fort Myers. This region is part of the ocean floor that's no longer underwater. It's flat, it's swampy, and it's sandy. And relict marine features such as ancient sand dunes and bars are still visible, miles from the modern Gulf. Water drains quickly downward through the sandy soils. But in some areas clay layers above the underlying limestone bedrock retards recharge to the aquifer. Swampy areas and standing water often result. In other areas only porous sand covers the limestone. Here rainwater can percolate directly into the limerock.

Tate's Hell State Forest is a good example of Gulf Coastal Lowlands, although it's not as soggy as it was before ditches were dug to drain the land. The Florida Division of Forestry has embarked on a long-term project to restore the region, which will also protect water quality in Apalachicola Bay. You can see the continuum between land and water if you take a drive along Highway 98 where it parallels the coastline in Franklin County.

At the saltwater shore, there's no sharp elevation difference between water and land, so as sea levels rise and fall, the shoreline moves easily. Barrier islands (St. Vincent, St. George, Dog) shift as the sea and the wind moves sand. The islands, like the mainland Gulf Coastal Lowlands, are at the mercy of the winds and waves. St. George Island State Park is a magnificent piece of barrier island that is accessible to the public.

From sea level up to about 100 feet in elevation above sea level, there is a gentle, nearly imperceptible slope from the shore to the base of the big step (the Cody Scarp) that separates the lowlands from the highlands in the ARROW region.

Some geologists like to subdivide the Gulf Coastal Lowlands into various subprovinces. In the ARROW region, the most distinctive subregion is the Woodville Karst Plain, most of which is in Wakulla County. Its boundary is not sharp. The Woodville Karst Plain extends westward roughly as far as Highway 319 at Crawfordville and then southwest to Panacea in Wakulla County. It extends eastward through Jefferson County.

Most of the eastern half of Wakulla County is in the Woodville Karst Plain. It's amazing and true: the Woodville Karst Plain is one of only three places on the entire planet that has such a wide array of karst features. The word "karst" refers to landscapes "generally underlain by limestone or dolostone, in which the topography is chiefly formed by the dissolution of rocks, and which may be characterized by sinkholes, sinking streams, closed depressions, subterranean drainage, and caves."

Because rainwater is slightly acidic, and because it becomes more acid as it travels down through the soil, it dissolves limestone. Given enough time (millions of years, that is), holes, tunnels, caverns, and caves develop in the limestone. Sometimes the overlying soil collapses, and sinkholes and depressions are the results. Water also finds its way back to the surface through these underground passageways, and that's how springs are formed. Because it's so easy for any liquid to get from the surface to the groundwater, karst areas are even more vulnerable to groundwater pollution than most areas in Florida. Wakulla Spring is one of the world's biggest single-vent springs, and its water quality is suffering from pollution that clouds its waters and feeds noxious plant growth. Scientists are hard at work to identify the sources of this pollution and to find ways to prevent Wakulla Spring's beauty from becoming a memory.

Another geomorphic region in the ARROW area is the Marianna Lowlands. The northern two-thirds of Jackson County is in this region. Its elevation is low compared to the surrounding geomorphic units, but it's not low for the same reason the Gulf Coastal Lowlands are low. The Marianna Lowlands were shaped by rivers and streams that both eroded its surface and left behind loads of sediment. The Marianna Lowlands has karst in common with the Woodville Karst Plain. Its subsurface limestone is pocked with sinkholes and depressions. Jackson Blue Spring is in the Marianna Lowlands, as is Falling Waters State Park in Washington County, where you can see a sinkhole 20 feet across and 100 feet deep. At Florida Caverns State Park north of Marianna, you can go right into the underground limestone on a tour of the dry caves there.

Slopes, ridges, and the Cody ScarpIn the ARROW region, transition zones between highlands and lowlands are classified as ridges, slopes, or scarps. The Cody Scarp separates highlands and hills to the north from coastal lowlands and karst plain to its south. (A "scarp," short for "escarpment," is a cliff, usually formed by erosion.) The Cody Scarp's westward limit is the Apalachicola River, from which it heads east and a little south well past Tallahassee and continues on into the peninsula. The Cody Scarp marks the shift in geology between the flat former seabed to the south and the hilly, river-sculpted, clay-dominated Tallahassee Hills to the north. A good place to see the Cody Scarp is in Tallahassee, along South Monroe Street between Gaines Street and the railroad overpass, where the elevation falls off steeply. Not all of the Cody Scarp is so dramatic, however; in places, it's hard to find.

In Liberty County and western Leon County, the Beacon Slope separates the Cody Scarp and Tallahassee Hills on the north from the Gulf Coastal Lowlands on the south. The Beacon Slope is about 200 feet above mean sea level on the north and grades gently down to 100 feet above mean sea level on the south. Low spots and sinkholes show that the limestone is not far from the surface of the Beacon Slope. Its origins are not clear, but it might have been shaped during periods of high sea levels during the Pleistocene.

West of the Apalachicola, in Jackson and Calhoun counties, the Gulf Coastal Lowlands and the Marianna Lowlands are separated by ridges and slopes. Grand Ridge is wedged between the Apalachicola and Chipola river valleys. West of the Chipola, the New Hope Ridge rises at the south boundary of the Marianna Lowlands. The elevations of these ridges are similar: 150 to 250 feet above sea level. They might share a common origin, too. At one time, all of north Florida from the Alabama line all the way to Putnam County on the St. Johns River is thought to have been one enormous highland zone. Streams and rivers have dissected and rearranged this ancient highland, and these two ridges are remnants of it. Erosion-resistant clayey sands have prevented the ridges from being worn down by rivers.

In Calhoun County, on the southern edge of the New Hope Ridge, the Fountain Slope drops from 180 feet above sea level on its northern border with the ridge to 100 feet on its southern border with the Gulf Coastal Lowlands. The Fountain Slope's eastern boundary is the Chipola River valley, and on the west it continues into Washington and Bay counties.

Highlands: Tallahassee Hills

The Tallahassee Hills geomorphic region covers most of Gadsden and Leon counties and extends into Jefferson County. Its surface sediments come from both river deposits and shallow seas. Geologists suspect that the Tallahassee Hills region is another remnant of the vast plain that, perhaps, once reached from southern Georgia into northern Florida. Streams have carved the region into smoothly rolling hills. In Liberty County, the elevation of the Hills reaches 250 feet above mean sea level.

The Hills come to an abrupt but spectacular end on the eastern bank of the Apalachicola River at Alum Bluff. One of Florida's premiere geological features, Alum Bluff is a nearly sheer cliff that rises nearly 150 feet above the river. Exposed here are formations dating back to the Miocene, nearly 24 million years ago. Take the Garden of Eden trail through The Nature Conservancy's Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve north of Bristol. The trail takes you to the top of Alum Bluff.

Note: The content of the website has not been updated since 2005. The site remains online for it's value as legacy content and is unlikely to be updated.