|

People Land Use Planning Water Resources Water Quantity Water Quality

|

Water Resources:

Water Quality

In This Section:

Stormwater | Effects on Fisheries | Sewage Treatment

So far, northwest Floridians have always enjoyed clean and abundant water, both on the surface and under the ground. As the region's population grows, that could change. As more open ground is paved and roofed over, more motor oil, trash, pet droppings, and lawn chemicals and fertilizers are washed by rainwater into creeks and bays. Nutrients from badly maintained septic tanks cause algae blooms and feed invasive aquatic plants that choke the springs and rivers. Unless development is handled with great care, these problems will only get worse.

Stormwater runoff (photo by Luther C. Goldman, courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) |

Some pollution comes from a particular source, such as the effluent pipe from a factory. These are called "point sources." Government regulations, new technologies, and advanced treatment of wastewater have reduced point source pollution in many parts of the United States.

Some of the most challenging water pollution problems come from "nonpoint sources." These are sources you can't point to and say, "See? Here's exactly where it's coming from." Nonpoint source pollution can't be remedied as easily as most point source pollution. The good news is that almost every one of us can do something to prevent the problem, whether it's using slow-release fertilizer, taking extra care to avoid spilling even a drop when you change your car's oil, or replacing your driveway with porous paving stones.

Stormwater Runoff

Rain that does not percolate into the soil “runs off” the land, hence the term “stormwater runoff.” Instead of traveling down into the aquifer, stormwater travels across the ground surface and flows into ponds, lakes, streams, rivers, and bays. As it travels, stormwater picks up all kinds of undesirable stuff:

In 1982, the State of Florida implemented a rule aimed at reducing stormwater runoff. All new developments are required to use a set of procedures called “best management practices” to minimize runoff during construction and to treat stormwater after construction. Best management practices include swales, retention ponds, detention ponds, and detention ponds with filtration. Yet pollution of our rivers and bays from stormwater runoff continues to be a serious problem in the region and throughout Florida.

In 2000, the Northwest Florida Water Management District (NWFWMD) published a study of stormwater runoff to Apalachicola Bay coming from Apalachicola, Carrabelle, Eastpoint, and Lanark Village. It reported:

“Nonpoint source pollution from urban areas and increasing development represents a serious problem that may be more devastating than more distant or regional sources of pollution originating upstream in the riverine watershed.”

The study found that the amount of pollution carried by stormwater into Apalachicola Bay is generally low, with the exception of coliform bacteria.

“However, increased levels of typical stormwater contaminants such as turbidity, total suspended solids, coliforms, nutrients, and some metals including copper, zinc and lead, are indicated with increased levels of development.”

The study concluded that stormwater discharges from Lanark Village and Carrabelle do not threaten the bay now, but the study did acknowledge that “Carrabele...is currently undergoing serious development pressures, and little control is being exercised to implement stormwater controls.”

Farther west, however, it's a different story. In Eastpoint, sewage contamination is getting into the bay. The culprits may include leaking septic tanks, the sewage treatment plant, dog pens, chicken coops, and pigs along the main channel. In Apalachicola, untreated stormwater runs straight into the bay. The City of Apalachicola's storm drainage system is antiquated and inadequate, and problems are anticipated to increase as the system continues to degrade.

The water management district is currently assisting Apalachicola and Eastpoint to design and install stormwater treatment projects.

Source: Marchman, G. L. 2000. An analysis of stormwater inputs to the Apalachicola Bay. Water Resources Special Report 00-01. Northwest Florida Water Management District, Havana, FL. Available as PDFs from http://www.state.fl.us/nwfwmd/pubs/apal_stormwater_inputs/apalachicola_stormwater_inputs.htm

Effects on Fisheries

Tonging oysters in Apalachicola Bay, 1986 (photo by Nancy Nusz, courtesy Florida Photo Archives) |

It doesn't take an expert to know that the quality of northwest Florida's fisheries depends on the quality of its waters. It is a challenge, though, to figure out exactly how poor water quality affect fisheries.

Take nutrients, for example. In some situations, the word “nutrient” means something good for you, like Vitamin C in orange juice. In surface waters, however, the word often implies too much of a good thing. Abnormally large quantities of nutrients (such as nitrogen or phosphorus) in a lake may not directly kill adult fishes, but too many nutrients may cause algae to “bloom.” (Yes, you're right. Algae don't produce flowers. The word “bloom” applied to algae just means they grow explosively.) Algae are important links in aquatic food chains, but, like most things, too much of a good thing can be awful. The thick coat of algae on the lake surface blocks sunlight needed by plants growing on the lake bottom, which eventually die. The dead plants accumulate as sediments and smother fish spawning and nursery areas, and the fish population crashes.

Clean water is vital for the shellfish industry in Apalachicola Bay, the source of 90 percent of Florida's oysters. Bacterial contamination coming from the Apalachicola River is, according to Marchman's report on stormwater runoff, "a real and dangerous threat to the seafood industry and the local economy of the area" and appears to come from both human and animal sources. When levels of coliform bacteria get too high, the bay is closed to oyster harvesting, and oyster harvesters, shuckers, and packers go hungry.

Water quality for oysters depends not only on chemistry and micro-organism populations but also by the flow of fresh water entering the bay. When the salt content of the bay's waters is high -- that is, when fresh water flows are low, during a drought, for instance -- predators that do not tolerate low salinity, such as mollusks and stone crabs, can invade the oyster bars and wreak havoc. The health of the oyster fishery in Apalachicola Bay will be deeply affected by the outcome of the ACF (Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint) water allocation controversy, which will determine the quantity and timing of fresh water flows reaching the bay.

Source: Allen, H. 1998. Water quality for fish. Fisheries Updates. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Division of Fisheries. http://www.floridafisheries.com/updates/ha21-h2o.html

Sewage Treatment

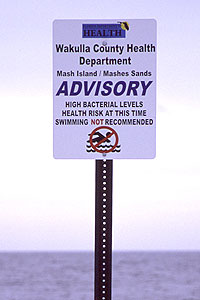

Bacteria from neglected septic tanks may have caused the closing of a popular beach in Wakulla County (photo by Karla Brandt) |

A common form of wastewater treatment, particularly in the rural parts of the ARROW region, is the septic tank, also called the “onsite sewage disposal system” or OSDS. The septic tank is attached to a drainfield, which relies on the soil to remove or deactivate bacterial, viral, and chemical contaminants so that they don't get into groundwater or surface water.

Studies have shown that, if properly located, constructed, operated, and maintained, septic tanks and drainfields provide low-cost and reliable treatment. But septic systems aren't suitable everywhere. Problems arise if:

When a septic system stops working, inadequately treated wastewater comes out of it and contaminates groundwater and surface water. In karst areas, this contaminated water can flow directly into the drinking water supply and right back up through a well into someone's kitchen.

The alternative is a central wastewater treatment plant. Household wastewater is sent through sewer pipes to the plant. Central treatment is the best option where the population is too dense for septic tanks and where soils are unsuitable for septic systems. Although sewage treatment plants don't always work perfectly, they are much easier to monitor than are hundreds of scattered septic tanks. The level of treatment carried out by these plants also varies, and with less treatment, more nutrients remain in the final product. Primary treatment filters out sand and large pieces from the wastewater. Secondary treatment creates the right conditions for bacteria to remove most of the remaining waste. Tertiary treatment takes out a lot of the leftover nutrients.

As the ARROW region's population increases, and as the population density rises in the region's towns and cities, central wastewater treatment capacity will become a hotter and hotter issue. Recently, the voters in Port St. Joe defeated a measure that would have required voter approval for extending sewer service outside the city limits. If the amendment had passed, the St. Joe Company's Windmark development in Gulf County would have had to build its own wastewater treatment system.

If your house is connected to a central treatment plant, be sure that the facility is being operated in a manner that is not detrimental to the groundwater or the waterways. If your house uses a septic system, be sure to get it inspected regularly, at least once every other year.

For more information on maintaining septic systems, see the onsite sewage home page posted by the Florida Department of Health.

Note: The content of the website has not been updated since 2005. The site remains online for it's value as legacy content and is unlikely to be updated.