|

People How Many People Quality of Life County Profiles |

People:

Quality of Life

In This Section:

Community Character | Noise | Light Pollution | Crime

“[O]ur ordinary surroundings, built and natural alike, have an immediate and a continuing effect on the way we feel and act, and on our health and intelligence. These places have an impact on our sense of self, our sense of safety, the kind of work we get done, the ways we interact with other people, even our ability to function as citizens in a democracy. In short, the places where we spend our time affect the people we are and can become.” --Tony Hiss

“It is as important to understand the design of the human habitat as it is to understand the ecology of a wetland.” --James Howard Kunstler

What is “quality of life"? In the context of land use, quality of life depends on how our surroundings affect our well-being, which is determined by such things as:

Community Character

“If you do not know where you are, you don't know who you are.” --Wendell Berry

“We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” --Winston Churchill

Places, like people, have personalities. Each has its own, and each is unique. What makes Quincy Quincy? What makes Bristol different from Panacea? Once you get to know a particular place, you can name things that make it what it is, that give it personality. These things usually cannot be measured or counted or otherwise quantified, but they are nevertheless vital to preserving a community's character.

Community character is strongly influenced by how people in a place make their living. Forestry has dominated the economy throughout the ARROW region, along with agriculture in the northern counties and commercial fishing along the coast. Imagine what Marianna would be like if there had been a big oil strike in Jackson County. Would it look and feel like Houston, Texas? And what if the paper mill had been built in Carrabelle instead of Port St. Joe? Playing these what-if games can help you focus on what gives your neighborhood its own particular character.

Travelers say that much of the United States is getting to look the same: same stores, same signs, same architecture, same parking lots. This increasing uniformity is in itself a type of community character, but it can obliterate the unique combination that makes a place one of a kind. Why live there when the same thing can be found in a larger town with more opportunities?

Community character is very easy to lose. As the ARROW region's economy shifts from forestry, fishing, and farming into building houses and providing services for new residents, the character of the region's communities changes too. The more new residents move in, the more commercial development will move in, too. Places will lose the character that attracted all those new residents in the first place.

Although land-use planning should consider community character, it often fails to do so. Traditional planning and zoning rules and procedures do not consider community character.

Citizens must make their opinions and preferences known during the planning process. By getting involved in planning efforts in your city or county, and by voicing your opinion on zoning issues that affect your neighborhood, you can help to shape the future character of your community.

Call your local planning department and get the meeting schedule for the groups that make decisions affecting you and your community. Then go and speak your mind, or write a letter or an e-mail.

Teton County, Wyoming, has a good plan for protecting community character.

Noise

The word "noise" is derived from the Latin word "nausea." Noise is unwanted sound. Each of us makes noise in one situation and suffer from the same noise in another situation. A couple of examples:

Noise can also affect health. Extreme noise causes temporary hearing loss, which becomes permanent with repeated exposure. Noise can interfere with sleep and metabolism, and it has been implicated in heart disease, high blood pressure, depression, and violent behavior. Chronic exposure to noise can decrease our productivity.

Noise is a very common form of pollution, especially in cities, where noise comes from roads, airports, factories, and construction sites. In rural and suburban areas, lawn mowers, leaf blowers, boom boxes, barking dogs, and crowing roosters may disrupt the serenity of your local neighborhood.

So what can be done about noise pollution? On an individual level, being a considerate neighbor is probably the best thing. Reduce the amount of sounds emanating from your yard that might be considered to be noise by your neighbors. For instance:

Nothing beats a face-to-face meeting with your neighbors to talk about problems before the situation gets out of hand. There are certain things that government officials can do to limit problems with noise pollution. These include:

The Northwest Florida Greenway may generate noise pollution once it is operational. This project will maintain a mixture of agricultural and public lands between Eglin Air Force Base and the Apalachicola River. The air space above those lands will be used for military training and testing, which will entail sonic booms and low-altitude flights.

For more information:

www.nonoise.org

World Health Organization Noise Fact Sheet

Guidelines for Community Noise (1999)

Light Pollution

"More of our children, and their children, should be able to look up at night and see that the Milky Way isn't only a candy bar."

--David L. Crawford

Badly placed and excessive outdoor lights obscure our view of the stars. Can we preserve the view and simultaneously use outdoor lighting? Yes!

Light pollution is a concern in the ARROW region because outdoor lights confuse migrating birds and hatchling sea turtles. These animals rely on the moon and stars to guide them. Bright artificial lights can disorient them. Hatchling sea turtles may end up on a road instead of in the ocean.

Other reasons why excessive outdoor lighting is a problem include:

What about security lighting? Studies by the US Department of Justice and the National Institute of Justice show no conclusive evidence that lighting prevents crime. Bad lighting creates dark shadows where thieves and others with bad intentions can lurk.

Lights at night (photo courtesy NESDIS/National Geophysical Data Center)

Good outdoor lighting enhances night vision, security, and safety, while simultaneously conserving energy. Such lighting

Using outdoor lighting wisely can save money, enhance safety, and ensure that migrating animals can find their way. It can also help preserve the view of the stars for us and for our children.

For more information:

International Dark-Sky Association

Campaign for Dark Skies

Crime

Crime is the most insidious threat to quality of life. One of the best ways to prevent crime is to know your neighbors, to know what's going on in your neighborhood, and to know what to do if you see something peculiar. Yet the fear of crime can isolate people and make them afraid to take action.

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement collects annual statistics on murder, sexual offenses, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft. Data are available at www.fdle.state.fl.us.

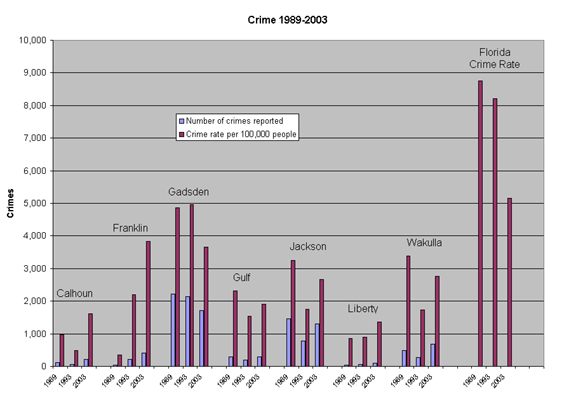

To compare the problem in different counties, crime rates are calculated as the number of crimes committed per 1,000 residents. Compared to the crime rate for entire state of Florida, crime rates in the ARROW region much lower.

Crime and crime rates for the seven ARROW counties and for Florida, 1989-2003 (graph constructed with data from: Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Crime in Florida, Florida uniform crime report, 2003 [Computer program]. Florida Statistical Analysis Center, FDLE, Tallahassee)

You can help prevent crime. An approach called “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design” (CPTED, pronounced Sep-Ted, for short) promotes architectural and landscape designs that increase safety, reduce opportunities for crime, discourage criminal behavior, and encourage people to keep an eye on things around them. A few design suggestions from CPTED include:

For more information on crime prevention:

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

Peel Police, Ontario

Sources of quotations:

Berry, Wendell T. Quoted by Wallace Stegner in The Sense of Place (1992, Random House, New York).

Churchill, W. Speech to the House of Commons, 28 October 1943 (www.winstonchurchill.org)

Crawford, D. 1989. Theft of the Night. National Academy of Sciences. Reproduced at www.darksky.org

Hiss, T. 1990. The experience of place: a completely new way of looking at and dealing with our radically changing cities and countryside. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, p xi.

Kunstler, J.H. 1996. Home from nowhere: remaking our everyday world for the 21st century. Simon & Schuster, New York, p. 173.

Note: The content of the website has not been updated since 2005. The site remains online for it's value as legacy content and is unlikely to be updated.