|

Regional History History of Timbering County Histories Oral Histories Calhoun County Gulf County Ronnie Brake Dave Maddox Tom Parker Jackson County Wakulla County |

History: Oral History of Gulf County

Ronnie Brake

Ronnie Brake in his gardens, 2005 |

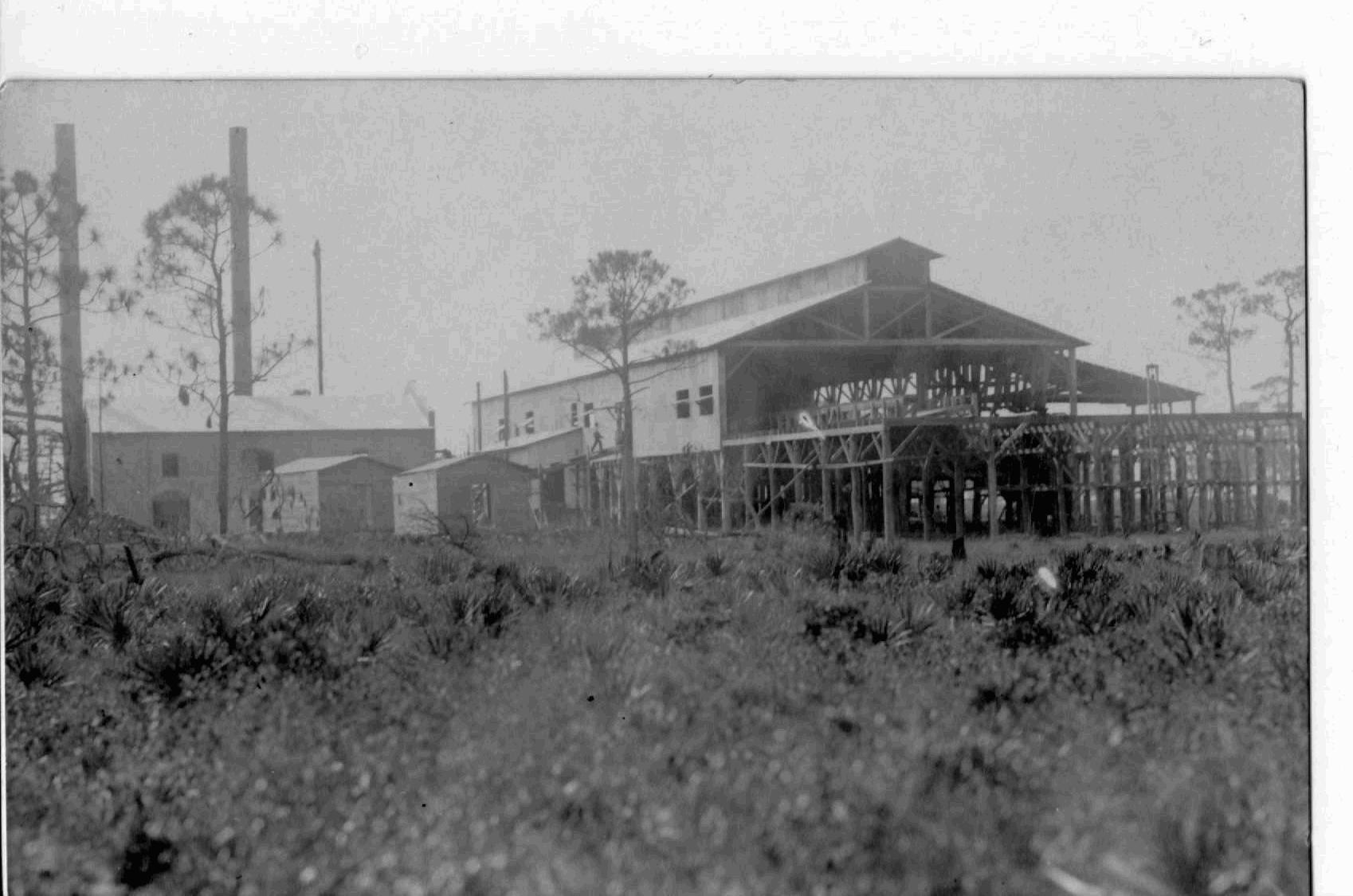

Ronnie Brake was born in 1946 in Kenney's Mill, a portion of Port St. Joe built for the workers of the St. Joe Lumber and Export Company's sawmill. Eight years earlier a huge sawmill had been constructed on an oak ridge facing the canal from the St. Joe Paper Company. According to local historian Wayne Childers, "the plans were to cut some 325,000,000 board feet of longleaf pine, 35,000,000 board feet of hardwoods and 50,000,000 board feet of cypress from the recently acquired St. Joe Paper Company lands."

Kenney's Mill contained 100-150 houses and grew to a community of 2,000-3,000 people and included a commissary, a Baptist Church, a boarding house, and a street lined with better houses for the supervisors.

Kenney's Mill |

Mr. Kenney's House |

Jake Brake, Ronnie's father, was born in Alabama and had lived in Thirteen Mile before moving to Kenney's Mill in 1943 where he worked loading logs on and off trucks and barges. Ronnie was one of 9 children, and his father provided for the family by hunting, fishing, gardening, and raising ducks and chickens as well working at the mill. The duck eggs were a prized ingredient for cakes. Today Ronnie still maintains a large garden behind his house in Highland View.

Ronnie Brake always loved to hunt, everything from deer and squirrels for food, to raccoons and gators for their skins and hides. He fished and gigged frogs, and both he and his father raised dogs for hunting deer and coons. Ronnie has observed many changes in hunting regulations and in the natural environment since the days when you could hunt just about anything anytime. He says today “there are no more woods, the deer are small—they get hunted before they mature--and the only place left to hunt is the Apalachicola River swamp.” He recalls the beauty of the Grassy Creek and all the little creeks and sloughs that connected the “Little” River (the Brothers River) to the “Big” River (the Apalachicola River). In earlier days, it was easy to travel by boat form the Brothers River to the Apalachicola River. Today, that's only possible when the water is high. Dredging of the river to keep the barge channel opened dumped sand in the woods and blocked many of the creeks. He noted that today “there are very few frogs” compared with the number in the past and that “all the chemicals dumped in the river have had to hurt the fish.” He also used to see a lot of sturgeon—“big, ugly things”—both on the river and when they'd enter the Gulf, but he hasn't seen a sturgeon in 20 years or maybe longer. He remembers when they used to catch them at Apalach in big-mesh nets.

Ronnie Brake has worked in commercial fishing all his life. In earlier years, he fished for the Raffields, pioneers in the fishing industry in Gulf and Franklin counties, and worked on the larger shrimp boats in the Gulf. Since 1996, he has worked for the St. Joe Shrimp Company based at Simmons Bayou, catching bait shrimp in the shallow grass beds of the bay. He prefers this work to the larger boats that would go out into the Gulf for 10, 12 or 15 days at a time.

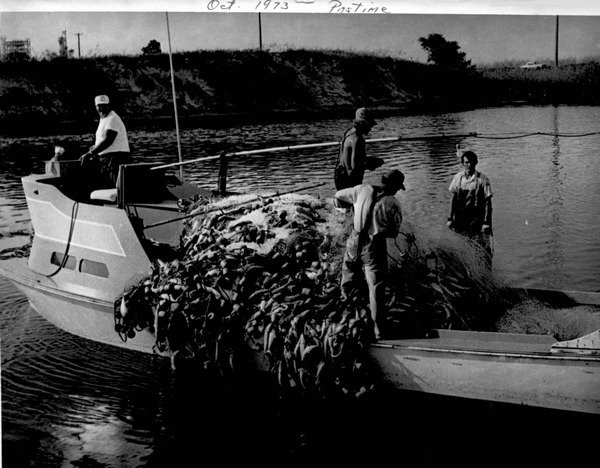

Source: Florida Photoarchives |

The above photo, taken in the early 1900s off the current U.S. Highway 98 in what is now Tyndall Air Force Base, depicts the early Raffield family fishing operation. Schools of mullet 3 miles long and 300 to 400 feet wide were common then and were caught in seine nets. The fish were preserved in layers of salt and packed in wooden barrels. The photo shows the bait catcher (small boat at right), the fishing boat with the seine net, men to gut and salt the fish in the shallow water, a pig to clean up the discarded fish parts, and a sailing vessel to transport the fish to market.

Source: Florida Photoarchives |

Th above picture was taken in 1973 and depicts the Raffied fishing boat The Pastime in Port St. Joe after it struck a school of mullet.

Baiting fishing on the bay is hard work and depends on the vagaries of the resource itself, the weather, and the market. His work ends in June and slowly begins again n August when the shrimp are so small, it's hard to imagine “how you can even get ‘em on a hook.” He works alone at night in an oyster boat with a frame for the net and a tank to keep the shrimp alive, keeping track of the numbers of shrimp caught with an abacus. Although he has a winch to pull in the net, the net will weigh from 75 to 100 pounds. The company he works for pays him by the thousand. On a good night he catches 5000-7000 shrimp. He goes out at dusk and returns at 1:30 or 2 in the morning. Storms on the bay are common, and sometimes “it gets so foggy, you can't even see the bow of the boat.” He has to rely on a compass or else “you can go right out the bay.”

St. Joe Shrimp Company, Simmons Bayou, 2005 |

He talks about the changes he has seen in commercial fishing. “It won't be many more years [and] you won't see a shrimp boat out there. You can't make a living anymore…fuel is so high…they're importing farm raised shrimp, you can't throw a cast net for mullet. The net ban affected everybody here who works on the water. People have moved to Mississippi and Louisiana where the law prohibits the use monofilament, but doesn't restrict the size of the net. Here they took it all away.”

In November 1994 Florida voters approved an amendment to the Florida Constitution known as the net ban that made use of entangling notes (gill and trammel nets) illegal in Florida waters. Other types of nets (seines, cast nets, and trawls) were restricted to a total area of net mesh to 500 square feet. A 2003 University of Florida IFAS report by Chuck Adams, Steve Jacobs, and Suzana Smith “What Happened After the Net Ban” concluded that the net ban “has had a dramatic impact on the nature of the near-shore commercial fisheries in Florida.” One-quarter of those interviewed had retired from commercial fishing altogether. Of the remaining, the percentage of those fishing full time dropped from 90 % to 70 %. The percentage of family income from fishing was reduced from 80% to 55% following the ban. According to the study, these families became far more dependent on nonfishing sources of income, most of which was contributed by wives.

Ronnie Brake is one of the last practitioners of an adaptation based on the varying bounty of the natural environment—hunting and gathering—that sustained humans on this earth for hundreds of thousands of years before the advent of agriculture. As Leo Lovel writes in Spring Creek Chronicles , commercial fishers are becoming extinct. “We're not breeding or able to raise any more commercial fisher people….A few of us still scrap up enough food from the sea to survive on, but just barely. None of us are encouraging our young to pursue this independent way of life.”

profile by Elizabeth D. Purdum

Note: The content of the website has not been updated since 2005. The site remains online for it's value as legacy content and is unlikely to be updated.